Initial synchronization

Overview of the Feature

What the feature is for:

Initial sync serves the following purposes:

Synchronizing from the last known node’s head (can be at genesis) to the highest finalized epoch known by the surrounding peers.

Synchronizing from the finalized checkpoint to the surrounding peers’ best known non-finalized epoch.

Fallback synchronization mechanism when node falls behind its peers while performing the regular synchronization.

Where the feature lives in Prysm: The feature is fully contained within the following folder/package: /beacon-chain/sync/initial-sync/

Technologies used: go-libp2p

Design Overview

What problems are being addressed:

The challenges for the initial sync implementers can be summarized as the following;

Peers surrounding the node can be bogus, non-responsive or even evil (that’s serving incoherent or wrong data on purpose). The trick is to make sure that blocks are being processed at a high pace, with good peers utilized to the fullest without danger of being eclipsed i.e. whether peer is considered good/bad is highly dependent on context and is dynamic in nature, so peer status should be updated regularly and a bad peer now may be a good choice to fetch from at some future moment.

Incoming block list is sequential, but in order to utilize available resources better and increase throughput, we need to fetch data concurrently. That can be redundant at times, and it is important to make sure that block processors are not caught in livelock (where they are just spinning on the very same redundant data), nor starving (when they are processing blocks at a higher pace than block fetchers are capable of providing).

When it comes to the non-finalized part of the chain, everything becomes a bit more complicated: at this point node’s known head is not finalized, thus can be changed, and initial sync algorithms should be aware of this (and re-request some previous range if necessary). This capability becomes crucial when it comes to long periods of non-finality where it’s critically important to allow nodes to synchronize to the highest epoch possible, yet backtrack (if necessary) to some previous ancestor to allow fork choice to select another branch to build upon.

Blocks are created during time slots, but some slots might have skipped/missing blocks, and the synchronization routine must be capable of finding the next non-skipped slot even if the gap is measured in thousands of slots.

Sometimes (especially exacerbated during long periods of non-finality) nodes can get stuck in an unfavourable fork, the synchronization routine must have capability to backtrack and explore other forks, ideally without too much time spent on spinning in that unfortunate fork.

Whenever there’s a problem with regular synchronization, initial synchronization serves as a fallback mechanism to catch up on peers. Therefore, it must be robust enough to proceed in spite of problems that caused the node to fall behind the peers in the first place.

High Level Design of the Solution

Essentially synchronization is split into two phases: from the state at which the node is started to the finalized checkpoint (as reported by majority of peers) and, then, if necessary, from that finalized checkpoint till the best known state (we have a minimum number of peers that are expected to support that state, before considering synchronization toward that head).

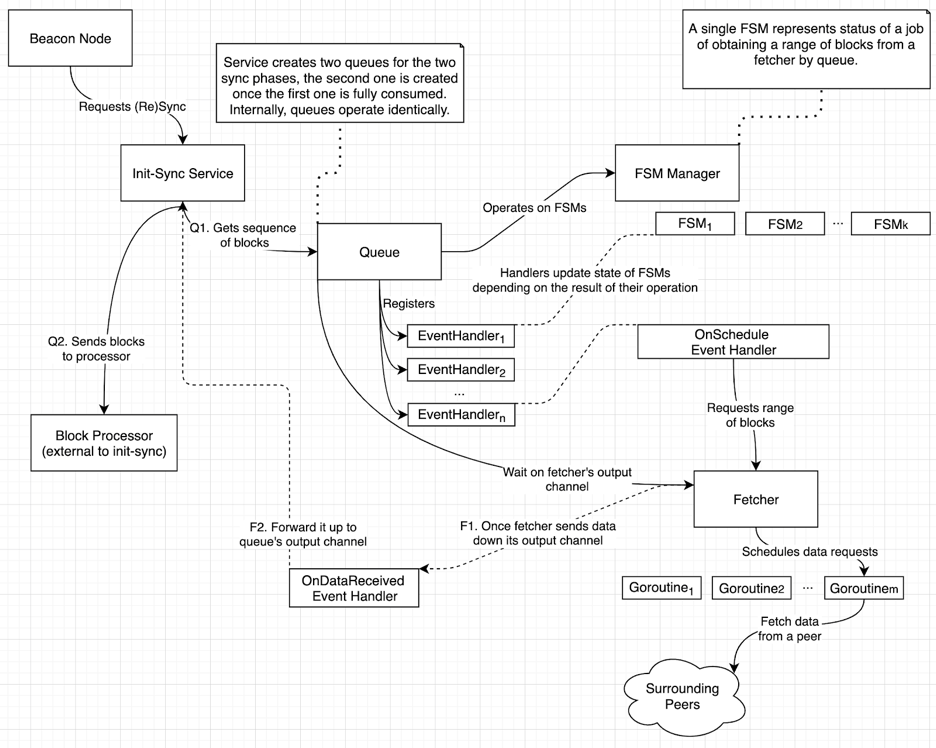

Both described phases utilize the very same synchronization mechanism: queue of blocks, which guarantees that incoming blocks will be in sequential order, block processors will never starve (the queue will always have some blocks waiting), and that with acceptable amount of redundant requests queue avoids livelocks by providing blocks that are capable of advancing the state.

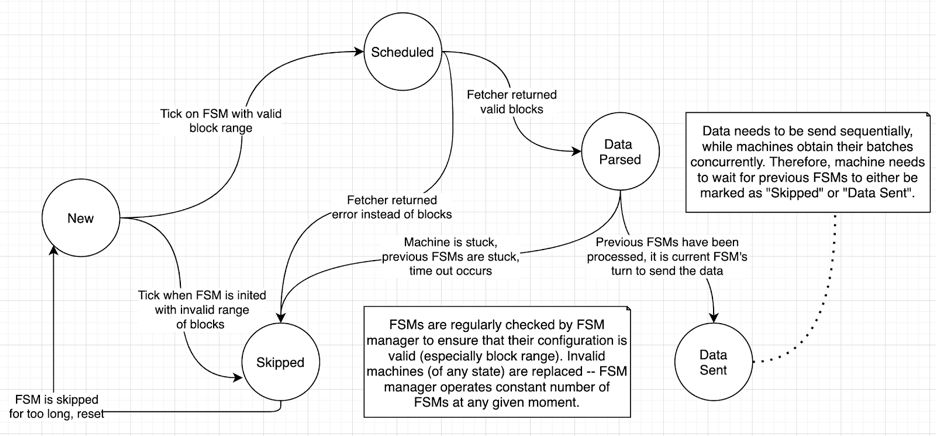

To keep track of the state, the queue utilizes finite state machines (FSMs): blocks are requested in batches, with each batch range of blocks assigned to one of available state machines, and within queue there’s a ticker that is constantly checking the state of each individual machine allowing them to apply actions to deterministically transit into the next state:

State(S) x Event(E) -> Actions (A), State(S')

(here E - is normally a tick event, and actions are selected from available event handlers depending on the initial state S).

FSMs are responsible for managing state transitions (fetch request queued, block batch requested, blocks received, data processed etc), but the actual fetching of data is handled by another major component of the init-sync system: block fetcher. This is done to decouple block queuing and actual block fetching: different state machines request different ranges concurrently. Of course, this may end up in some redundancy (when the earliest machine’s blocks are on some wrong fork and the next FSMs cannot proceed without resetting and re-requesting data of that first machine).

Service Design Diagram

FSM State Transitions Diagram

Architectural Overview

Structure of the feature (is it a service, a tool, a background routine?)

Initial synchronization is implemented as a separate service, loadable into service registry.

Components of the feature

Initial Synchronization Service

Available synchronization functionality is exposed via initalsync.Service, with two major methods: Start() and Resync(). The former is responsible for initialization of the service and the first synchronization after the node’s initial start and the latter is called when beacon node falls behind during the normal synchronization, and needs to resync using a more robust initial synchronization mechanism.

Another purpose of the service object is to be the glue between blocks queue and blocks processor: it makes sure that the queue is started and blocks received are forwarded to the processor.

See: service.go, round_robin.go

Blocks Queue

Blocks queue is the core component managing higher level block fetching from the surrounding peers.

Queue operates in the following manner:

When started, queue creates the internal fetcher service, which is responsible for lower level data fetching functionality i.e. queue manages the overall scheduling process, while blocks fetcher is responsible for talking to peers, requesting and processing their data (see blocks_queue.go:newBlocksQueue. Block fetcher exposes the output channel which the queue keeps waiting on up until all the necessary blocks are fetched, at that point the queue closes the fetcher's context thus closing that sub-service as well see: blocks_queue.go:loop.

In order to keep FSMs as lightweight as possible, queue registers event handlers with itself instead of registering them with each individual machine. Each handler function accepts FSM as an argument (thus event handlers are fully aware on which machine they operate on).

Queue relies on the FSM manager to create/remove FSMs. In order to allow concurrent scheduling of different batches of blocks, queue relies on several machines (currently 8). FSMs are used to track the state of different block request ranges (whether blocks in that range have been requested, already fetched, sent down the pipeline etc).

Once the fetcher is initialized and event handlers are registered, the queue enters an event listening loop, with only two available event types:

TickandData Received. TheTickevent is nothing more than a time ticker triggering different events handlers on FSMs (depending on their current state) on a regular basis (currently every 200 milliseconds). TheData receivedevent is triggered asynchronously on read from the output channel of the fetcher i.e. when the fetcher returns some data to parse and pass over to block processors.

Available events handlers:

On schedule: this event handler is triggered when a

Tickevent occurs on a machine in aNewstate.On data received: this event handler is triggered when a

Data Receivedevent occurs on a machine (if machine is not inScheduledstate, incoming data is ignored).On ready to send: this event handler is triggered when a

Tickevent occurs on a machine withData Parsedstate i.e. machine that has incoming data placed into it.On a stale machine: this event handler is triggered when a

Tickevent occurs on an unresponsive machine, the main purpose of this handler is to mark the machine as skipped, so thatOn a skipped machinehandler resets it.On a skipped machine: this event handler is triggered when a

Tickevent occurs on a stuck machine, that's a machine that stays in a given state for too long, and is marked asSkipped, this handler is responsible for resetting such machines.

See: blocks_queue.go, Queue.onScheduleEvent(), Queue.onDataReceivedEvent(), Queue.onReadyToSendEvent(), Queue.onProcessSkippedEvent(), Queue.onCheckStaleEvent()

FSM Manager and FSMs

Each FSM (see fsm.go:stateMachine) has the following data associated with it:

Start Slot: beginning of the range of blocks to pull into a given machine. The end slot is determined by the batch size, which is a predefined constant (currently 64).

Peer ID: identifies a peer that was used to fetch blocks into a given state machine; provided by fetcher via its output channel.

Blocks: fetched blocks; provided by the fetcher via its output channel.

FSM Manager is a container used to group machines together, for easier management and traversal. It is queue’s responsibility to make sure that Start Slot uniquely identifies the machine: there’s no point in having a machine with the same start slots, as machines are fetching batches of a constant size starting from the start slot, therefore machines with the same start slot will essentially fetch the same block range (albeit, possibly, from the different peers). Of course sometimes such a redundancy is unavoidable: in cases when the beacon node’s head cannot be advanced, machines with slots equal to that of some previously used machines can be spawned (see how machines are reset in onProcessSkippedEvent() event handler).

While event handlers operate on FSMs, they are not registered with machines themselves but with the queue, this is done for reasons of efficiency (machines are constantly removed and re-added, so are kept as simple as possible). When an event occurs (for example Tick event occurs every 200 milliseconds), each known FSM is passed to the corresponding event handler, depending on FSM’s current state. Here is the list of event handlers, required FSM start states and their corresponding handlers:

| Event | Required FSM state | Event Handler |

|---|---|---|

| Tick | New | Queue.onScheduleEvent() |

| Tick | Data parsed | Queue.onReadyToSendEvent() |

| Tick | Skipped | Queue.onProcessSkippedEvent() |

| Tick | Sent | Queue.onCheckStaleEvent() |

| Data Received | Scheduled | Queue.onDataReceivedEvent() |

The above table is easy to read: for example it is easy to see that in order for an FSM to be passed to onDataReceivedEvent() handler, it must be in a Scheduled state and Data Received event must occur (that’s fetcher should write something into its output channel).

Below is a state transition table (depending on input there might be several possible transitions for a given event -- only one of which is valid, as our FSMs are deterministic):

| State/Event | New | Scheduled | Data Parsed | Skipped | Data Sent |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tick | Scheduled Skipped | Data Sent Skipped | New | New Skipped | |

| Data Received | Data Parsed New |

Refer to FSM state transitions diagram for further details.

See: fsm.go:stateMachineManager

Machines lifetime

When queue operates, FSMs are constantly being created and removed:

- Whenever a queue has less than a predefined number of machines (currently 8), a new machine is added.

- Once a machine is outdated (its data is processed, or it features a block range that has already been passed by the currently known head, or it is in a stuck or invalid state), it is removed from the FSM manager.

This is done to optimize the runtime and make code more simple to understand (had we decided to reuse the machines it would have required a lot of orchestration code - but right now, queue implementation is very simple and gets the job done).

So, whenever we need to implement some complex algorithm it almost always has to do with creating a new state machine of a particular configuration. For instance, see Handling Skipped Slots section and how finding the first non-skipped slot is implemented using a machine with a start slot set to some high future epoch.

Being able to algorithmically select a range of blocks (which will be reset if stuck, and if it gets blocks, those blocks will be eventually pushed into the queue and towards the block processors -- automatically) is one of the main benefits of using FSMs.

See: blocks_queue_utils.go:resetFromFork() and blocks_queue_utils.go:resetFromSlot()

Blocks Fetcher

The fetcher component (see blocks_fetcher.go:blocksFetcher) is responsible for handling p2p communication, and does the actual data requesting and fetching. It is a very simple component operating in the following way:

Fetcher manages two channels: one for incoming fetching requests and the other for sending fetched data back to requesters. All this is done asynchronously, of course!

Fetcher is smart enough to honour rate limits and while being highly concurrent, never requests at a higher pace than is allowed by Prysm beacon nodes (see getPeerLock()). So, fetching nodes should never receive a bad score from fellow Prysm peers (while it is theoretically possible that other clients still consider our fetcher aggressive, in reality Prysm has one of the strictest limits, thus in practice this has never happened).

All the low level details (like checking that enough peers are available, filtering out less useful peers, handling p2p errors) of data requesting is abstracted within the fetcher service.

See: blocks_fetcher.go, blocks_fetcher_peers.go, blocks_fetcher_utils.go

Noteworthy code in the feature

There are several very interesting add-ons to the main synchronization procedure, making it more robust and useful. In this section, we will briefly cover them (feel free to dive into the code deeper -- it should be easy to follow).

Backtracking procedure

Normally, there are no more than a handful of non-finalized epochs, and once initial synchronization is complete, the regular synchronization is capable of proceeding by obtaining new blocks, validating them, and applying fork-choice rule. But occasionally, the whole network is unable to reach consensus and forked branches start to occur, and can even get quite long. This is especially prevalent during test networks (see Medalla Incident post-mortem), where there’s no real ether at stake.

Regular synchronization cannot handle such fork branching, and node eventually falls behind the highest expected slot (if counting time slots from the genesis up to the current clock time). Once that happens, the system falls back to initial synchronization, which needs to be able to not only synchronize with the majority of known peers, but handle the case when that majority is dynamic i.e. be capable to backtrack from some unfavourable fork, which is no longer voted for by the current majority of known peers (while it was supported by previous majority just 10 minutes ago!).

Our backtracking algorithm is pretty simple (code is abridged, see full version here:)

// findFork queries all peers that have higher head slot, in an attempt to find

// ones that feature blocks from alternative branches. Once found, peer is

// further queried to find a common ancestor slot.

func (f *blocksFetcher) findFork(..., slot uint64) (*forkData, error) {

// some details are skipped..

// Select peers that have a higher head slot, and potentially blocks

// from a more favourable fork.

_, peers := f.p2p.Peers().BestNonFinalized(1, epoch+1)

f.rand.Shuffle(len(peers), func(i, j int) {

peers[i], peers[j] = peers[j], peers[i]

})

// Query all found peers, stop on peer with alternative blocks,

// and try backtracking.

for i, pid := range peers {

fork, err := f.findForkWithPeer(ctx, pid, slot)

if err != nil {

continue

}

return fork, nil

}

return nil, errNoPeersWithAltBlocks

}

Essentially, all we are doing is querying our peer list for peers with a non-finalized known slot higher than that which our node was able to progress to. Then, out of those peers, the peers list is randomized and they are queried to find a peer with blocks our node hasn’t as yet seen. Once such a peer is found, we need to backtrack (hence the name!) on that peer from the slot starting at our node’s head backwards in history until the common ancestor block is found (or until the predefined limit is reached, to avoid infinite/overly long loops). Once a common ancestor is found, node tries to build on top of that alternative fork. While seemingly trivial, this procedure has worked extremely well.

Handling skipped blocks

At each slot a block can be proposed. If this doesn’t happen, the block is considered as skipped. There might be lots of consecutive skipped blocks, but our queue has only 8 FSMs (so, can look no further than 8x64 = 512 blocks “into the future”). How do you overcome such a limitation, where the normal queue range of vision is 512 next slots, and the first non-skipped block is 10K+ slots away?

A simple trick is used: when all machines are in Skipped state, meaning we are stuck, the first 7 machines are reset normally (the first machine's starting slot is the current known head slot, the second machine is +64 slots, and so on, and so forth), but the last state machine is reset from a slot, possibly very far in future, where the first non-skipped block is found. So, if the last machine is set to start fetching within range where the next non-skipped block lives, then it will be able to fetch that block, and thus advance our node’s head slot. The only problem is finding that starting slot for this last FSM, and doing so efficiently i.e. without simply querying each and every slot up until we find a non-empty one (which can be 10K+ slots away).

We’ve devised an algorithm that is capable of looking ahead 50K+ slots (instead of only 512), and even further (for 50K we have unit tests proving the statement):

nonSkippedSlotAfter(slot):

head := chain head on which peers agree (we filter and shuffle peers)

check fist n (currently n = 10) epochs, fully, slot by slot

if non-skipped slot found return, if not then resort to random sampling

for every epoch in (slot+n*32 to best known head]:

select and check random slot (one for each epoch)

if slot is non-skipped log it and break out of the loop

with found non-skipped slot:

find surrounding epochs and pull all the blocks

(to find the first non-skipped slot)

when block with slot > than argument slot is found, return it

And the corresponding implementation can be found in blocks_fetcher_utils.go:nonSkippedSlotAfter, here it signature:

// nonSkippedSlotAfter checks slots after the given one in an attempt to find

// a non-empty future slot.

// For efficiency only one random slot is checked per epoch, so returned slot

// might not be the first non-skipped slot. This shouldn't be a problem, as

// in case of adversary peer, we might get incorrect data anyway, so code that

// relies on this function must be robust enough to re-request, if no progress

// is possible with a returned value.

func (f *blocksFetcher) nonSkippedSlotAfter(slot uint64) (uint64, error) {}

The procedure is quite optimized, for instance, within a single request, node samples 16 future epochs are at once (so the pace is 16x32=512 blocks/request, when looking for a non-skipped slot). Hence even non-skipped slots which are significantly in the futre are found very quickly.

See: blocks_queue.go:onProcessSkippedEvent()

Utilizing peer scorer

Since we are dealing with a public decentralized network, we cannot assume that each peer behaves correctly, and there might be bogus, unresponsive, or even malicious peers.

In order to avoid being stuck with a single unresponsive peer, our first fetcher implementation shuffled peers before selecting one to fetch data from. We have improved upon this method and now score peers on their behaviour and increase the probability of selecting high scoring peers, thus utilizing our mesh more efficiently.

We have quite sophisticated scoring mechanisms already in place, and we’re continuingly building on them. Currently, the peer scorer service is able to track peer’s performance (on how many requests, how many useful blocks -- that’s blocks advancing the head -- have been returned). Peers scoring higher will have a better chance of being selected (see blocks_fetcher_peers.go for full code):

// filterPeers returns a transformed list of peers, weight sorted by scores

// and capacity remaining.

// List can be further constrained using peersPercentage, where only

// percentage of peers are returned.

func (f *blocksFetcher) filterPeers(... peers []peer.ID, peersPercentage float64) []peer.ID {

// Sort peers using both block provider score and, custom, capacity

// based score (see peerFilterCapacityWeight if you want to give

// different weights to provider's and capacity scores).

// Scores produced are used as weights, so peers are ordered

// probabilistically i.e. peer with

// a higher score has a higher chance to end up higher in the list.

scorer := f.p2p.Peers().Scorers().BlockProviderScorer()

peers = scorer.WeightSorted(f.rand, peers, func(

peerID peer.ID, blockProviderScore float64) float64 {

remaining, capacity := float64(f.rateLimiter.Remaining(peerID.String())), float64(f.rateLimiter.Capacity())

// When capacity is close to exhaustion, allow less performant peers

// to take a chance.

// Otherwise, there's a good chance the system will be forced to

// wait for the rate limiter.

if remaining < float64(f.blocksPerSecond) {

return 0.0

}

capScore := remaining / capacity

overallScore := blockProviderScore*(1.0-f.capacityWeight) + capScore*f.capacityWeight

return math.Round(overallScore*scorers.ScoreRoundingFactor) / scorers.ScoreRoundingFactor

})

return trimPeers(peers, peersPercentage)

}

Not only do we filter by score, we also take into account the remaining capacity of a peer (capacity being the number of blocks left, before the rate limiter will be triggered and requests to the peer are blocked for a short period of time until capacity is restored).

Testing

Unit tests and mocks, how to write tests for the feature: Since initial synchronization interacts heavily with the P2P layer, we rely on mocks to simulate network mesh. The easiest way to start the test is to use initializeTestServices():

// Get chain, network, and database objects.

// You can provide blocks of your node as a second param.

// Surrounding peers are defined in the third param.

mc, p2p, db := initializeTestServices(t, []uint64{}, []*peerData{})

See, TestBlocksQueue_Loop() as an example of testing block syncing as a whole.

If you need more control on node’s known state, or on peer’s known state, we also have the following helper methods for that:

// Setup database:

beaconDB := dbtest.SetupDB(t)

// Setup network layer:

p2p := p2pt.NewTestP2P(t)

// Setup beacon chain sequence (128 blocks):

chain := extendBlockSequence(t, []*eth.SignedBeaconBlock{}, 128)

genesisBlock := chain[0]

require.NoError(t, beaconDB.SaveBlock(context.Background(), genesisBlock))

genesisRoot, err := genesisBlock.Block.HashTreeRoot()

require.NoError(t, err)

// Initialize beacon state:

st := testutil.NewBeaconState()

mc := &mock.ChainService{

State: st,

Root: genesisRoot[:],

DB: beaconDB,

FinalizedCheckPoint: ð.Checkpoint{

Epoch: finalizedEpoch,

Root: []byte(fmt.Sprintf("finalized_root %d", finalizedEpoch)),

},

}

Now, you’re able to populate node’s chain with any blocks you need (including forked or skipped ones):

// Populate database with blocks with part of the chain,

// orphaned block will be added on top.

for _, blk := range chain[1:84] {

parentRoot := bytesutil.ToBytes32(blk.Block.ParentRoot)

// Save block only if the parent root is already in the database or cache.

if beaconDB.HasBlock(ctx, parentRoot) || mc.HasInitSyncBlock(parentRoot) {

require.NoError(t, beaconDB.SaveBlock(ctx, blk))

require.NoError(t, st.SetSlot(blk.Block.Slot))

}

}

Finally, time to configure peer’s blocks:

finalizedSlot := uint64(82)

finalizedEpoch := helpers.SlotToEpoch(finalizedSlot)

// Connect peer that has all the blocks available. You can have a peer with

// forked or missed blocks -- just update the chain param.

allBlocksPeer := connectPeerHavingBlocks(t, p2p, chain, finalizedSlot, p2p.Peers())

defer func() {

p2p.Peers().SetConnectionState(allBlocksPeer, peers.PeerDisconnected)

}()

Since we have prepared (and customized) all the necessary mocks, time to setup queue and fetcher services:

// Setup fetcher:

fetcher := newBlocksFetcher(

ctx,

&blocksFetcherConfig{

chain: mc,

p2p: p2p,

db: beaconDB,

},

)

fetcher.rateLimiter = leakybucket.NewCollector(6400, 6400, false)

// Queue should be able to fetch the whole chain.

queue := newBlocksQueue(ctx, &blocksQueueConfig{

blocksFetcher: fetcher,

chain: mc,

highestExpectedSlot: uint64(len(chain) - 1),

mode: modeNonConstrained,

})

For even better illustration on customized setups, please, see the following tests:

Runtime testing and usage

To run unit tests using bazel:

bazel test //beacon-chain/sync/initial-sync:go_default_test --test_arg=-test.v --test_output=streamed --test_arg=-test.failfast --nocache_test_results --test_filter=

The --test_filter can be empty (all tests will then be run), or specify a pattern to match:

| --test_filter | Component to be tested |

|---|---|

| TestBlocksQueue | All blocks queue tests. |

| TestBlocksFetcher | All blocks fetcher tests. |

| TestStateMachine | All FSM related tests. |

| TestService | All init-sync service tests. |

To run tests using vanilla Go, just use go test (to understand the reasons for passing the develop tag see our DEPENDENCIES):

go test ./beacon-chain/sync/initial-sync -v -failfast -tags develop -run TestBlocksQueue

When it comes to system and integration testing, generally one is expected to do it manually: run the beacon node and see whether it was able to sync from genesis to the latest head.

Variations include: stopping and restarting, stopping for a long time and then restarting, switching off access to the internet etc etc. Here is one way to do it:

# Remove previous data:

rm -r ~/prysm/beaconchaindata ~/prysm/network-keys

# Assuming you have geth node running locally, run init-sync on holesky

bazel run //beacon-chain -- --datadir=$HOME/prysm \

--verbosity=debug \

--p2p-max-peers=500 \

--execution-endpoint=$HOME/Library/Ethereum/holesky/geth.ipc \

--enable-debug-rpc-endpoints --holesky